New Hampshire – The Poem

I met a lady from the South who said

(You won’t believe she said it, but she said it):

“None of my family ever worked, or had

A thing to sell.” I don’t suppose the work

Much matters. You may work for all of me.

I’ve seen the time I’ve had to work myself.

The having anything to sell is what

Is the disgrace in man or state or nation.

I met a traveler from Arkansas

Who boasted of his state as beautiful

For diamonds and apples. “Diamonds

And apples in commercial quantities?”

I asked him, on my guard. “Oh, yes,” he answered,

Off his. The time was evening in the Pullman.

I see the porter’s made your bed,” I told him.

I met a Californian who would

Talk California—a state so blessed,

He said, in climate, none had ever died there

A natural death, and Vigilance Committees

Had had to organize to stock the graveyards

And vindicate the state’s humanity.

“Just the way Stefansson runs on,” I murmured,

“About the British Arctic. That’s what comes

Of being in the market with a climate.”

I met a poet from another state,

A zealot full of fluid inspiration,

Who in the name of fluid inspiration,

But in the best style of bad salesmanship,

Angrily tried to make me write a protest

(In a verse I think) against the Volstead Act.

He didn’t even offer me a drink

Until I asked for one to steady him.

This is called having an idea to sell.

It never could have happened in New Hampshire.

The only person really soiled with trade

I ever stumbled on in old New Hampshire

Was someone who had just come back ashamed

From selling things in California.

He’d built a noble mansard roof with balls

On turrets, like Constantinople, deep

In woods some ten miles from a railroad station,

As if to put forever out of mind

The hope of being, as we say, received.

I found him standing at the close of day

Inside the threshold of his open barn,

Like a lone actor on a gloomy stage—

And recognized him, through the iron gray

In which his face was muffled to the eyes,

As an old boyhood friend, and once indeed

A drover with me on the road to Brighton.

His farm was “grounds,” and not a farm at all;

His house among the local sheds and shanties

Rose like a factor’s at a trading station.

And he was rich, and I was still a rascal.

I couldn’t keep from asking impolitely,

Where had he been and what had he been doing?

How did he get so? (Rich was understood.)

In dealing in “old rags” in San Francisco.

Oh, it was terrible as well could be.

We both of us turned over in our graves.

Just specimens is all New Hampshire has,

One each of everything as in a showcase,

Which naturally she doesn’t care to sell.

She had one President. (Pronounce him Purse,

And make the most of it for better or worse.

He’s your one chance to score against the state.)

She had one Daniel Webster. He was all

The Daniel Webster ever was or shall be.

She had the Dartmouth’ needed to produce him.

I call her old. She has one family

Whose claim is good to being settled here

Before the era of colonization,

And before that of exploration even.

John Smith remarked them as he coasted by,

Dangling their legs and fishing off a wharf

At the Isles of Shoals, and satisfied himself

They weren’t Red Indians but veritable

Pre-primitives of the white race, dawn people,

Like those who furnished Adam’s sons with wives;

However uninnocent they may have been

In being there so early in our history.

They’d been there then a hundred years or more.

Pity he didn’t ask what they were up to

At that date with a wharf already built,

And take their name. They’ve since told me their name—

Today an honored one in Nottingham.

As for what they were up to more than fishing—

Suppose they weren’t behaving Puritanly,

The hour had not yet struck for being good,

Mankind had not yet gone on the Sabbatical.

It became an explorer of the deep

Not to explore too deep in others’ business.

Did you but know of him, New Hampshire has

One real reformer who would change the world

So it would be accepted by two classes,

Artists the minute they set up as artists,

Before, that is, they are themselves accepted,

And boys the minute they get out of college.

I can’t help thinking those are tests to go by.

And she has one I don’t know what to call him,

Who comes from Philadelphia every year

With a great flock of chickens of rare breeds

He wants to give the educational

Advantages of growing almost wild

Under the watchful eye of hawk and eagle

Dorkings because they’re spoken of by Chaucer,

Sussex because they’re spoken of by Herrick.

She has a touch of gold. New Hampshire gold—

You may have heard of it. I had a farm

Offered me not long since up Berlin way

With a mine on it that was worked for gold;

But not gold in commercial quantities,

Just enough gold to make the engagement rings

And marriage rings of those who owned the farm.

What gold more innocent could one have asked for?

One of my children ranging after rocks

Lately brought home from Andover or Canaan

A specimen of beryl with a trace

Of radium. I know with radium

The trace would have to be the merest trace

To be below the threshold of commercial;

But trust New Hampshire not to have enough

Of radium or anything to sell.

A specimen of everything, I said.

She has one witch—old style. She lives in Colebrook.

(The only other witch I ever met

Was lately at a cut-glass dinner in Boston.

There were four candles and four people present.

The witch was young, and beautiful (new style),

And open-minded. She was free to question

Her gift for reading letters locked in boxes.

Why was it so much greater when the boxes

Were metal than it was when they were wooden?

It made the world seem so mysterious.

The S’ciety for Psychical Research

Was cognizant. Her husband was worth millions.

I think he owned some shares in Harvard College.)

New Hampshire used to have at Salem

A company we called the White Corpuscles,

Whose duty was at any hour of night

To rush in sheets and fool’s caps where they smelled

A thing the least bit doubtfully perscented

And give someone the Skipper Ireson’s Ride.

One each of everything as in a showcase.

More than enough land for a specimen

You’ll say she has, but there there enters in

Something else to protect her from herself.

There quality makes up for quantity.

Not even New Hampshire farms are much for sale.

The farm I made my home on in the mountains

I had to take by force rather than buy.

I caught the owner outdoors by himself

Raking up after winter, and I said,

“I’m going to put you off this farm: I want it.”

“Where are you going to put me? In the road?”

“I’m going to put you on the farm next to it.”

“Why won’t the farm next to it do for you?”

“I like this better.” It was really better.

Apples? New Hampshire has them, but unsprayed,

With no suspicion in stern end or blossom end

Of vitriol or arsenate of lead,

And so not good for anything but cider.

Her unpruned grapes are flung like lariats

Far up the birches out of reach of man.

A state producing precious metals, stones,

And—writing; none of these except perhaps

The precious literature in quantity

Or quality to worry the producer

About disposing of it. Do you know,

Considering the market, there are more

Poems produced than any other thing?

No wonder poets sometimes have to seem

So much more businesslike than businessmen.

Their wares are so much harder to get rid of.

She’s one of the two best states in the Union.

Vermont’s the other. And the two have been

Yokefellows in the sap yoke from of old

In many Marches. And they lie like wedges,

Thick end to thin end and thin end to thick end,

And are a figure of the way the strong

Of mind and strong of arm should fit together,

One thick where one is thin and vice versa.

New Hampshire raises the Connecticut

In a trout hatchery near Canada,

But soon divides the river with Vermont.

Both are delightful states for their absurdly

Small towns—Lost Nation, Bungey, Muddy Boo,

Poplin, Still Corners (so called not because

The place is silent all day long, nor yet

Because it boasts a whisky still—because

It set out once to be a city and still

Is only corners, crossroads in a wood).

And I remember one whose name appeared

Between the pictures on a movie screen

Election night once in Franconia,

When everything had gone Republican

And Democrats were sore in need of comfort:

Easton goes Democratic, Wilson 4

Hughes 2. And everybody to the saddest

Laughed the loud laugh the big laugh at the little.

New York (five million) laughs at Manchester,

Manchester (sixty or seventy thousand) laughs

At Littleton (four thousand), Littleton

Laughs at Franconia (seven hundred), and

Franconia laughs, I fear—-did laugh that night–

At Easton. What has Easton left to laugh at,

And like the actress exclaim “Oh, my God” at?

There’s Bungey; and for Bungey there are towns,

Whole townships named but without population.

Anything I can say about New Hampshire

Will serve almost as well about Vermont,

Excepting that they differ in their mountains.

The Vermont mountains stretch extended straight;

New Hampshire mountains Curl up in a coil.

I had been coming to New Hampshire mountains.

And here I am and what am I to say?

Here first my theme becomes embarrassing.

Emerson said, “The God who made New Hampshire

Taunted the lofty land with little men.”

Another Massachusetts poet said,

“I go no more to summer in New Hampshire.

I’ve given up my summer place in Dublin.”

But when I asked to know what ailed New Hampshire,

She said she couldn’t stand the people in it,

The little men (it’s Massachusetts speaking).

And when I asked to know what ailed the people,

She said, “Go read your own books and find out.”

I may as well confess myself the author

Of several books against the world in general.

To take them as against a special state

Or even nation’s to restrict my meaning.

I’m what is called a sensibilitist,

Or otherwise an environmentalist.

I refuse to adapt myself a mite

To any change from hot to cold, from wet

To dry, from poor to rich, or back again.

I make a virtue of my suffering

From nearly everything that goes on round me.

In other words, I know wherever I am,

Being the creature of literature I am,

I shall not lack for pain to keep me awake.

Kit Marlowe taught me how to say my prayers:

“Why, this is Hell, nor am I out of it.”

Samoa, Russia, Ireland I complain of,

No less than England, France, and Italy.

Because I wrote my novels in New Hampshire

Is no proof that I aimed them at New Hampshire.

When I left Massachusetts years ago

Between two days, the reason why I sought

New Hampshire, not Connecticut,

Rhode Island, New York, or Vermont was this:

Where I was living then, New Hampshire offered

The nearest boundary to escape across.

I hadn’t an illusion in my handbag

About the people being better there

Than those I left behind. I thought they weren’t.

I thought they couldn’t be. And yet they were.

I’d sure had no such friends in Massachusetts

As Hall of Windham, Gay of Atkinson,

Bartlett of Raymond (now of Colorado),

Harris of Derry, and Lynch of Bethlehem.

The glorious bards of Massachusetts seem

To want to make New Hampshire people over.

They taunt the lofty land with little men.

I don’t know what to say about the people.

For art’s sake one could almost wish them worse

Rather than better. How are we to write

The Russian novel in America

As long as life goes so unterribly?

There is the pinch from which our only outcry

In literature to date is heard to come.

We get what little misery we can

Out of not having cause for misery.

It makes the guild of novel writers sick

To be expected to be Dostoievskis

On nothing worse than too much luck and comfort.

This is not sorrow, though; it’s just the vapors,

And recognized as such in Russia itself

Under the new regime, and so forbidden.

If well it is with Russia, then feel free

To say so or be stood against the wall

And shot. It’s Pollyanna now or death.

This, then, is the new freedom we hear tell of;

And very sensible. No state can build

A literature that shall at once be sound

And sad on a foundation of well-being.

To show the level of intelligence

Among us: it was just a Warren farmer

Whose horse had pulled him short up in the road

By me, a stranger. This is what he said,

From nothing but embarrassment and want

Of anything more sociable to say:

“You hear those hound dogs sing on Moosilauke?

Well, they remind me of the hue and cry

We’ve heard against the Mid – Victorians

And never rightly understood till Bryan

Retired from politics and joined the chorus.

The matter with the Mid-Victorians

Seems to have been a man named John L. Darwin.”

“Go ‘long,” I said to him, he to his horse.

I knew a man who failing as a farmer

Burned down his farmhouse for the fire insurance,

And spent the proceeds on a telescope

To satisfy a lifelong curiosity

About our place among the infinities.

And how was that for otherworldliness?

If I must choose which I would elevate —

The people or the already lofty mountains

I’d elevate the already lofty mountains

The only fault I find with old New Hampshire

Is that her mountains aren’t quite high enough.

I was not always so; I’ve come to be so.

How, to my sorrow, how have I attained

A height from which to look down critical

On mountains? What has given me assurance

To say what height becomes New Hampshire mountains,

Or any mountains? Can it be some strength

I feel, as of an earthquake in my back,

To heave them higher to the morning star?

Can it be foreign travel in the Alps?

Or having seen and credited a moment

The solid molding of vast peaks of cloud

Behind the pitiful reality

Of Lincoln, Lafayette, and Liberty?

Or some such sense as says how high shall jet

The fountain in proportion to the basin?

No, none of these has raised me to my throne

Of intellectual dissatisfaction,

But the sad accident of having seen

Our actual mountains given in a map

Of early times as twice the height they are—

Ten thousand feet instead of only five—

Which shows how sad an accident may be.

Five thousand is no longer high enough.

Whereas I never had a good idea

About improving people in the world,

Here I am overfertile in suggestion,

And cannot rest from planning day or night

How high I’d thrust the peaks in summer snow

To tap the upper sky and draw a flow

Of frosty night air on the vale below

Down from the stars to freeze the dew as starry.

The more the sensibilitist I am

The more I seem to want my mountains wild;

The way the wiry gang-boss liked the logjam.

After he’d picked the lock and got it started,

He dodged a log that lifted like an arm

Against the sky to break his back for him,

Then came in dancing, skipping with his life

Across the roar and chaos, and the words

We saw him say along the zigzag journey

Were doubtless as the words we heard him say

On coming nearer: “Wasn’t she an i-deal

Son-of-a-bitch? You bet she was an i-deal.”

For all her mountains fall a little short,

Her people not quite short enough for Art,

She’s still New Hampshire; a most restful state.

Lately in converse with a New York alec

About the new school of the pseudo-phallic,

I found myself in a close corner where

I had to make an almost funny choice.

“Choose you which you will be—a prude, or puke,

Mewling and puking in the public arms.”

“Me for the hills where I don’t have to choose.”

“But if you had to choose, which would you be?”

I wouldn’t be a prude afraid of nature.

I know a man who took a double ax

And went alone against a grove of trees;

But his heart failing him, he dropped the ax

And ran for shelter quoting Matthew Arnold:

“‘Nature is cruel, man is sick of blood’:

There’s been enough shed without shedding mine.

Remember Birnam Wood! The wood’s in flux!”

He had a special terror of the flux

That showed itself in dendrophobia.

The only decent tree had been to mill

And educated into boards, be said.

He knew too well for any earthly use

The line where man leaves off and nature starts.

And never overstepped it save in dreams.

He stood on the safe side of the line talking—

Which is sheer Matthew Arnoldism,

The cult of one who owned himself “a foiled

Circuitous wanderer,” and “took dejectedly

His seat upon the intellectual throne”—

Agreed in ‘frowning on these improvised

Altars the woods are full of nowadays,

Again as in the days when Ahaz sinned

By worship under green trees in the open.

Scarcely a mile but that I come on one,

A black-checked stone and stick of rain-washed charcoal.

Even to say the groves were God’s first temples

Comes too near to Ahaz’ sin for safety.

Nothing not built with hands of course is sacred.

But here is not a question of what’s sacred;

Rather of what to face or run away from.

I’d hate to be a runaway from nature.

And neither would I choose to be a puke

Who cares not what he does in company,

And when he can’t do anything, falls back

On words, and tries his worst to make words speak

Louder than actions, and sometimes achieves it.

It seems a narrow choice the age insists on

How about being a good Greek, for instance)

That course, they tell me, isn’t offered this year.

“Come, but this isn’t choosing—puke or prude?”

Well, if I have to choose one or the other,

I choose to be a plain New Hampshire farmer

With an income in cash of, say, a thousand

(From, say, a publisher in New York City).

It’s restful to arrive at a decision,

And restful just to think about New Hampshire.

At present I am living in Vermont.

My New Hampshire

I think, each one of us has a New Hampshire in their life, a place where we want to go after all this is over and want to live peacefully ever after.

There was a small village at one end of the Great Thar Desert. One of my aunts lives there. I had a few of my cousins also living in that village. They had big farms there. I do not remember the size, but they extended as far as we could see or run. We enjoyed our visits there. Thar is full of sand dunes. We would, during the day, make sandcastles under the sheds (air conditioning did not matter at that time). We’d divide ourselves into two groups and have a competition as to who will make a prettier sandcastle (of course to be judged by our parents). In the evening, we would take rides on their horses or the bullock cart and go to the farms. Since we were young guests, the farmers working there would prepare local snacks for us. We enjoyed the local snacks in the middle of the fields, with the soothing smell of freshly watered soil. And the night ended with my cousin’s grandmother telling us the stories from her younger days, till extremely late at night. Even today I love playing with sand there.

Back then, it was a dream. After I finish my studies (I wanted it to get finished really soon, I was completely not interested in books), I wanted to buy a small farm, with my house in the middle of it. Not in the same village (that village was my New Hampshire) but a similar village nearby (which would be my Vermont). I had planned everything. For the Kharif crop, I would grow millets and groundnuts (a combination of a staple and legume). And, for the rabi crop a combination of wheat and mustard. My favorite was the yellow-colored mustard fields, though. I would also keep cows in my stable. They would also provide for fertilizers. Have you seen how innocent those baby calves look? Have you ever seen their dark doe eyes?

Each one of us has those childhood dreams. And then you are hit hard by a force called life. You get too engrossed in the routine, and these dream gets piled up in some corner of your heart.

Then there are days when you feel you are too caged, you simply want to break free. On one such day, I was talking to one of my best friends since childhood. I said, “I want to dispose-off everything here go to a village start the life afresh”. Just like Robert Frost, I want to take a farm (it would be awesome if I could take land by force and not buy it). Grow my stuff, not in commercial quantities, and get my income (a very basic one) from publishing activity here. I don’t have really big needs (at least that is what I believe).

But she rejected my idea instantly. According to her, I have lived three decades of my life in a metro city and village would be a completely different thing. For her, I am too accustomed to the routine of getting up early, rushing to work, working without looking at the watch, maybe watching a movie at the weekend, or maybe taking time out to writing something silly. And, according to her the biggest hurdle in adjusting there would be the people there. She thinks I would never find people there who could work equally rigorously for me as I am used to.

But I don’t think people are a problem. The problem for me would be the growing urbanization in the villages. The houses in the villages are no longer the same. They have some degree of automation as any city houses. And my same cousins (or their kids) don’t see their backyards where we used to build mud houses for months, because apparently, it is too hot out there. You don’t find the old rural villages any longer.

New Hampshire – Poem Summary

Robert Frost had been a great admirer of nature and its beauty throughout his life, and his work has been quite a reflection of it. He had also been a traveler throughout his lifetime.

This poem is sort of an ode to the city of New Hampshire. In this poem, Frost has mentioned his conversation with a lot of people, most of them who have traveled a lot. And none of them speak in favor of New Hampshire. Or is this their shallowness speaking?

People disapprove of the unbusinesslike nature of the city. New Hampshire, according to Frost, has a “specimen” of everything, but it does not produce anything in commercial quantities. His own farm produces gold, but only enough to make engagement and wedding rings for his family. But according to him, “selling” or “having anything to sell” is such a “disgrace”. It reduces the artistic value of that thing. Frost also jokes about how he acquired his farm (its previous seller did not sell it to him, he took it by force). Nothing is for sale in New Hampshire.

Some of the people Frost met also criticized New Hampshire for the people. But Frost claims that he has made the best of friends ever at this place only. Someone from Massachusetts also ridiculed New Hampshire for its “lofty” people. But to this Robert Frost says, if he had a chance to elevate the height of either people of New Hampshire or its mountains, he would elevate the mountains. (This is also a good reflection of his love for nature and its beauty.)

The best part about New Hampshire is that it has enough art. According to Robert Frost, New Hampshire has plenty of exceptionally fine artists living there. So many, that it becomes difficult to have a good value for their literary work.

There is also a question in the poem about choosing to be a “prude” or a “puke”. Frost doesn’t want to choose any. Being a “prude” would be demeaning to his love for nature. And being a “puke” would mean he doesn’t care about anything but his business. He is an environmentalist and wouldn’t do anything to harm nature. And when questioned, like pukes, he wouldn’t give justification to prove his wrongdoings right.

Robert Frost is being highly critical of society in the poem. One such evidence of his criticism is the election and the survey on it with figures.

The poet mentions the expectations of writers to be “Dostoievskis”, who brought the change of the political system in Russia as a fact of the actual international politics. The other such fact mentioned by R. Frost is the Volstead Act. One more allusion on the actual international politics is „Polyanna”:

“If well it is with Russia, then feel free

To say so or be stood against the wall

And shot. It’s Pollyanna now or death.

This, then, is the new freedom we hear tell of;

And very sensible.”

The new regime made a political cleanup.

If there was enough value that he could obtain for his art in New Hampshire, he wouldn’t have left the place. This probably is the most peaceful place.

Form & Structure

The form of the poem is blank verse since R. Frost wrote it in rows of 10-11 syllables,

with changing of an emphatic and non-emphatic syllable, without rhymes. They so make the iambic inclination as in the Shakespeare dramas. Originally the blank verse was introduced into England by Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey (1517 – 1547) a poet, and Sir Thomas Wyatt (1503 – 1542). They introduced the styles and meters of the humanist poets of Italy. It was then used by Marlowe and Shakespeare. Later it was renewed by Shelley, Keats, Wordsworth, (1st part of the XIXth. century, English Romanticism), and Tennyson (1809 – 1892). After their literature, R. Frost renewed the blank verse in the dawn of the XX. century.

The publication of the poem: 1923. It reflects on the growing anti-Semitism, that is

grounded by mentioning Ahaz, the biblical king, ancestor of Jesus in House of David (second-last strophe).

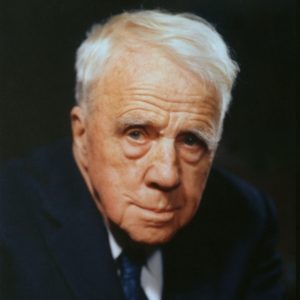

Robert Frost

Robert Lee Frost (March 26, 1874 – January 29, 1963) was an American poet. His work was initially published in England before it was published in America. Known for his realistic depictions of rural life and his command of American colloquial speech, Frost frequently wrote about settings from rural life in New England in the early twentieth century, using them to examine complex social and philosophical themes.

Frost was honored frequently during his lifetime and is the only poet to receive four Pulitzer Prizes for Poetry. He became one of America’s rare “public literary figures, almost an artistic institution.” He was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 1960 for his poetic works. On July 22, 1961, Frost was named poet laureate of Vermont.

It is said that Robert frost purchased a farm in New Hampshire and did farming for a few years (farming during the day and writing at night). After it proved unsuccessful, he started working as a school teacher. A few years later he sailed with his family to Great Britain (where he found good publishers and demand for his literary work).

To read more about Robert Frost, click here.

Places Mentioned In The Poem

- New Hampshire

- South (With respect to the lady from the south who along with her family members have never worked)

- Arkansas, Pullman City (about the traveler whom he met who boasted about the apples and diamond production in his city)

- California (a city blessed with the best climate, that no one falls sick there)

- British Arctic (being similar to California in terms of climate)

- Constantinople (About the man he met in New Hampshire, who build a Mansard with roofs like those found in Constantinople)

- Brighton (Mention of a drover on the road to Brighton)

- San Francisco (About the man who got rich by selling “rags” in San Francisco)

- Isles of Shoals.

The Isles Shoals extends between the States Maine and New Hampshire as if being forked. I think, it refers to the 2×2 choices before the poet: 1) between the 2 states, Vermont and New Hampshire; 2) between the messy, chaotic, and cruel society, and that of rural life… - Nottingham (The names of people in New Hampshire, being honored one in Nottingham)

- Philadelphia (About a person who comes from Philadelphia each year with a rare breed of chicken)

- Berlin (“Berlin way” is mentioned with reference to the time, maybe when he was in Berlin)

- Andover or Canaan (In reference to the beryl brought by his children from there)

- Colebrook (In reference to the “old-styled witch”, who lives there)

- Boston (With reference to the new-styled witch whom he met at a “cut-glass” dinner in Boston).

“a cut-glass dinner” with the „4 candles and the 4 peoples present”: an allusion on the high society of the USA, the 2nd is that of a symbol of an inverse vigil. - Salem (Where the company named “White Corpuscles” was)

- Vermont (One of the two best states, and the state where Robert Frost is currently living)

- Connecticut (a trout hatchery near Canada)

- Franconia (A place where Robert Frost once traveled and saw a movie)

- New York, Manchester, Littleton, Easton

- Samoa, Russia, Ireland, England, France, and Italy

- Connecticut, Rhode Island, New York, or Vermont (On choosing New Hampshire over these places)

- Moosilauke (A mountain in New Hampshire, where hound dogs sing)

- Stefansson

Vilhjalmur Stefansson (November 3, 1879 – August 26, 1962) was an Icelandic American Arctic explorer and ethnologist. He was born in Manitoba, Canada, and died at the age of 82.

To read more about him, click here. - Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, and Millard Fillmore. He was one of the most prominent American lawyers of the 19th century and argued over 200 cases before the U.S. Supreme Court between 1814 and his death in 1852. Throughout his career, he was a member of the Federalist Party, the National Republican Party, and the Whig Party.

To read more about him, click here. - John Smith

John Smith (baptized. 6 January 1580 – 21 June 1631) was an English soldier, explorer, colonial governor, Admiral of New England, and author. He played an important role in the establishment of the colony at Jamestown, Virginia, the first permanent English settlement in America in the early 17th century. He was a leader of the Virginia Colony between September 1608 and August 1609, and he led an exploration along the rivers of Virginia and the Chesapeake Bay, during which he became the first English explorer to map the Chesapeake Bay area. Later, he explored and mapped the coast of New England. He was knighted for his services to Sigismund Báthory, Prince of Transylvania, and his friend Mózes Székely.

To read more about John Smith, click here. - Skipper Ireson (Reference to John Greenleaf Whittier’ poem “Skipper Ireson’s Ride”)

The Ireson Ride had happened indeed in 1808, Whittier wrote his ballad of a real story. In addition, the name Ireson is a speaking name in the literature: ‘the Son of Wrath’. - Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803 – April 27, 1882) was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a champion of individualism and a prescient critic of the countervailing pressures of society, and he disseminated his thoughts through dozens of published essays and more than 1,500 public lectures across the United States.

To read more about him, click here. - Kit Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe, also known as Kit Marlowe 26 February 1564 – 30 May 1593), was an English playwright, poet, and translator of the Elizabethan era. Modern scholars count Marlowe among the most famous of the Elizabethan playwrights and based upon the “many imitations” of his play Tamburlaine consider him to have been the foremost dramatist in London in the years just before his mysterious early death. Some scholars also believe that he greatly influenced William Shakespeare, who was baptized in the same year as Marlowe and later became the pre-eminent Elizabethan playwright. Marlowe’s plays are the first to use blank verse, which became the standard for the era, and are distinguished by their overreaching protagonists. Themes found within Marlowe’s literary works have been noted as humanistic with realistic emotions, which some scholars find difficult to reconcile with Marlowe’s “anti-intellectualism” and his catering to the taste of his Elizabethan audiences for generous displays of extreme physical violence, cruelty, and bloodshed.

To read more about Kit Marlowe, click here. - Dostoievskis

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (11 November 1821 – 9 February 1881), sometimes transliterated Dostoyevsky, was a Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist, and journalist. Dostoevsky’s literary works explore human psychology in the troubled political, social, and spiritual atmospheres of 19th-century Russia, and engage with a variety of philosophical and religious themes. His most acclaimed works include Crime and Punishment (1866), The Idiot (1869), Demons (1872), and The Brothers Karamazov (1880). Dostoevsky’s body of works consists of 12 novels, four novellas, 16 short stories, and numerous other works. Many literary critics rate him as one of the greatest psychological novelists in world literature. His 1864 novella Notes from Underground is considered to be one of the first works of existentialist literature.

To read more about him, click here. - Bryan (William Jennings Bryan who retired from politics to join chorus)

- John L. Darwin (This is maybe a joke by Robert Frost against Darwin’s theory of evolution. He was much in favor of spiritual evolution rather than “cruel-universe theory” suggested by Darwin).

- Lincoln, Lafayette, and Liberty

- Matthew Arnold

Matthew Arnold (24 December 1822 – 15 April 1888) was an English poet and cultural critic who worked as an inspector of schools. He was the son of Thomas Arnold, the celebrated headmaster of Rugby School, and brother to both Tom Arnold, literary professor, and William Delafield Arnold, novelist and colonial administrator. Matthew Arnold has been characterized as a sage writer, a type of writer who chastises and instructs the reader on contemporary social issues. He was also an inspector of schools for thirty-five years, and supported the concept of state-regulated secondary education.

To read more about him, click here. - Ahaz

Ahaz, an abbreviation of Jehoahaz II (of Judah), “Yahweh has held” was the twelfth king of Judah, and the son and successor of Jotham. Ahaz was 20 when he became king of Judah and reigned for 16 years.

Ahaz is portrayed as an evil king in the Second Book of Kings (2 Kings 16:2).

Edwin R. Thiele concluded that Ahaz was co-regent with Jotham from 736/735 BC, and that his sole reign began in 732/731 and ended in 716/715 BC. William F. Albright has dated his reign to 744–728 BC.

The Gospel of Matthew lists Ahaz of Judah in the genealogy of Jesus. He is also mentioned in Isaiah 14:28.

To read more about him, click here.

- At the end of the poem, we see the “bottom line of the poem” borrowing from the epigrams: he lives not in New Hampshire but in Vermont… These means are characteristic of epigrams.

Other Mentions

- Volstead Act

The National Prohibition Act, known informally as the Volstead Act, was enacted to carry out the intent of the 18th Amendment (ratified January 1919), which established prohibition in the United States. The Anti-Saloon League’s Wayne Wheeler conceived and drafted the bill, which was named for Andrew Volstead, Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, who managed the legislation.

To read more about the Volstead Act, click here. - Dartmouth College (which is needed to produce people like Daniel Webster)

- Red Indians (Referred to people of North Hampshire being not the Red Indians, as remarked by John Smith)

- New Hampshire Gold

- Beryl, is a mineral composed of beryllium aluminum cyclosilicate with the chemical formula Be3Al2Si6O18. Well-known varieties of beryl include emerald and aquamarine. Naturally occurring, hexagonal crystals of beryl can be up to several meters in size, but terminated crystals are relatively rare. Pure beryl is colorless, but it is frequently tinted by impurities; possible colors are green, blue, yellow, red (the rarest), and white. Beryl is also an ore source of beryllium. Read more here.

- White Corpuscles (The company at Salem)

White Corpuscules: originally they were founded for guarding ethics; in town

California, state Calif., they were true, anti-black men chauvinist committees, racism. And the poet uses irony by intermingling the denotations of the expression. By this irony, he makes sensible the denounce aspect of racism.

Read more here. - Lariats (A long light rope, as of hemp or leather, used with a running noose to catch livestock or with or without the noose to tether grazing animals)

- Yokefellow (A strong companion)

- Pollyanna (an excessively cheerful or optimistic person.)

Polyanna, i.e. Yasnaya Polyana was originally the latifundia of the Russian noble family. - Tolstoy, i.e., Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy, the writer (1828 – 1910) was a land tenure and he confessed the idea of Pan-Slavism. In addition, he emancipated his serfs, he was alone in contemporary Russia with this. His kinship wanted him to manifest as mad. The name of his land, Yasnaya Polyana means Serene / Clear Fields. So, the poet, Robert Frost made here two important allusions to international politics. These can be seen in the last lines: “This is then, the new freedom we hear tell of,”.

- Birnam Wood (a wood in central Scotland. In Shakespeare’s play Macbeth, the witches tell Macbeth that he will not be defeated until Birnam Wood comes to Dunsinane. Later, Macduff’s army hides behind branches cut from the wood as they advance to attack Macbeth’s castle at Dunsinane, so it appears as though the wood is moving.)

To read the best poems by the finest poets ever, click here.

Amazing poem!

New Hampshire reminds me of my grandparents’ village and our home there. ❤️❤️